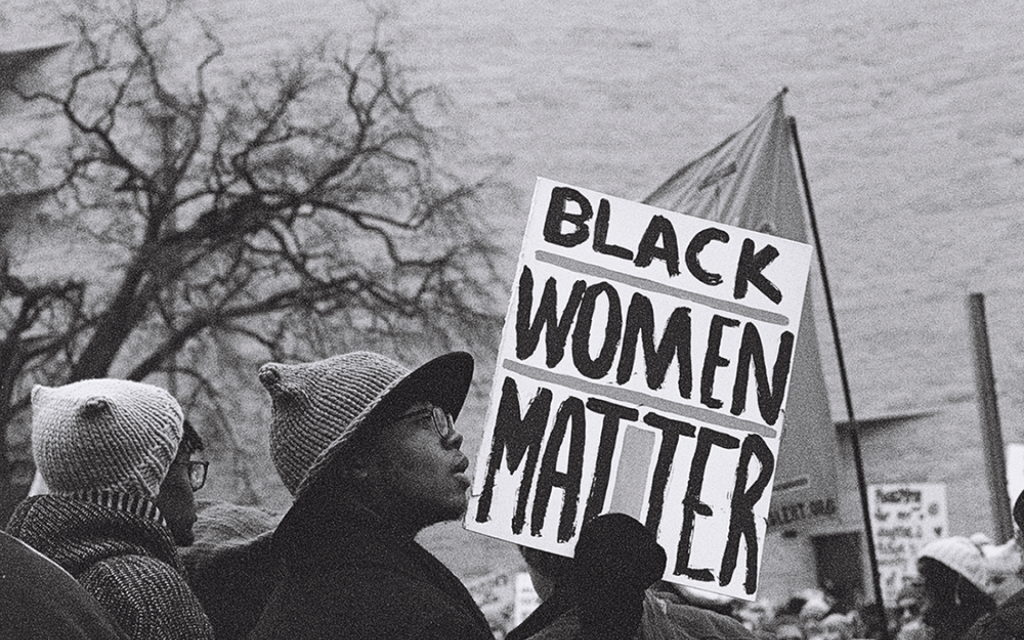

Black feminism (or Afro-feminism) is a branch of feminist theory that focuses on African-American women’s situations and experiences (Weida). Its prototype first emerged in the 19th century due to slavery, but it was not until the 1960s that Black feminism was heavily engaged in a political movement. As left-wing activist Mary Ann Weathers suggests, ‘All women suffer oppression, even white women, particularly poor white women, and especially Indian, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Oriental and Black American women whose oppression is tripled by any of those as mentioned earlier. (Weathers)’. In the 1960s, at the start of the second wave of feminism, the prevalence of Black feminism was raised as a formal topic of the oppression of people of colour over white women.

However, why black and coloured women, compared with their white counterparts, tended to suffer from more severe oppression and discrimination under patriarchy? Patricia Collins and Kimberle Crenshaw gave us the answers in their 1989 and 1991 work, respectively. While the former focused on the birth of Black feminists’ thoughts and their significance (Collins), the latter carefully examined the roles of structure, politics and representation in terms of oppressing Black women in a patriarchal system (Crenshaw). More importantly, Crenshaw also coined the term ‘intersectionality’ to illustrate that an individual’s identity and social position are not determined by one factor but are up to various elements, including gender, social class, ethnicity, etc (Deckha). Therefore, as feminine individuals, black women have to struggle with the oppression and harm from the patriarchal system. As ethnical minorities, they also have to cope with racial discrimination, and those together bring them a ‘distinctive set of experiences that offers a different view of material reality than that available to other groups. (Collins)’

In the United States, black women, who are usually the head of their households, are not only at a disadvantage in terms of income, but they also do not have access to the benefits of society (e.g., free health care) (Institute for Women’s Policy Research). In Henry Mitchell and Nicholas Lester’s view, their experiences are transformed into symbols in a conceptual framework that internalises social injustices and roots their systems of thought (Collins). In other words, most black women who are being exploited are not aware of their situation. Instead, their personal experiences ‘justify’ the validity of the structure within where they are. This created a paradoxical situation: few black female scholars were able to enter research at institutions of higher learning before 1950. Those who did were not standing up for their compatriots but instead fostering the development of authority mechanisms within a framework defined by white males (Collins).

In Crenshaw’s perspective, black women are oppressed in the following ways. In terms of structural intersectionality, which concerns the group’s social position within the structure (Walby et al.), Crenshaw used the instances of the language barrier; the contempt that rape crisis centres have for black women proves the perilous situation they face. Notably, she also mentioned the case that some women are reluctant to leave their partners who abused them in order to avoid deportation. Although radical feminists may claim that this result is the product of patriarchy that puts women in a corner, arguably, the victims have the agency to decide which route to go and evaluate the consequences and interests of both approaches.

As for political intersectionality, it refers to the dilemma of an individual who is both black and female in the face of multiple political groups to which she belongs. Crenshaw cited Nilda Rimonte’s findings as the evidence:

Nilda Rimonte, director of Everywoman’s Shelter in Los Angeles, points out that in the Asian community, saving the honor of the family from shame is a priority. Unfortunately, this priority tends to be interpreted as obliging women not to scream rather than obliging men not to hit.

This illustrates the intersectionality in which oppressed women can only give up part of their own interests for the glory of the so-called ‘family’ in exchange for the stability of another part of their self-identity. This practice is amplified by the media to create stereotypes of black women in the public’s views. These stereotypes, in turn, subsequently change attitudes and practices when dealing with black women and further produce such perceptions (Ramasubramanian et al.).

At this point, a third kind of intersectionality, the representational intersectionality, is elicited. Crenshaw defined that as ‘both how these images are produced through a confluence of prevalent narratives of race and gender, as well as a recognition of how contemporary critiques of racist and sexist representation marginalize women of color‘. For instance, blacks ‘have long been portrayed as more sexual, more earthy, more gratification-oriented‘. This representation creates an alarming fact: more than 18 per cent of African-American women have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime (West and Johnson). More seriously, as sharply pointed out by Crenshaw, the prevalence of misogynistic imagery (e.g. movies, rap music) had made black women ‘learn(ing) that their value lies between their legs‘ while failing to realise that ‘the sexual value of women, unlike that of men, is a depletable commodity; boys become men by expending theirs, while girls become whores‘.

Fortunately, more and more media representation of independent black women brings us new possibilities. Not only are authors such as Maya Angelou and bell hooks using words to fight for their rights, but more and more women are using rap music, previously used to denigrate and stigmatise them, as a tool to fight back against. For instance, African-British rapper Little Simz wrote, ‘Tell ’em you’re nothin’ without a woman, no/Woman to woman, I just wanna see you glow/Tell ’em what’s up (Ajikawo)’ and used black women from different regions as symbols to thank women who inspired her.

These changes are exciting. As for the future of black feminism, I am sure it will be on a positive path at a time when more and more minorities have the right to express themselves.

Works Cited

Ajikawo, Simbiatu. “Little Simz – Woman Lyrics.” Genius, 6 May 2021, genius.com/Little-simz-woman-lyrics.

Collins, Patricia Hill. “The Social Construction of Black Feminist Thought.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 14, no. 4, University of Chicago Press, July 1989, pp. 745–73. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1086/494543.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review, vol. 43, no. 6, JSTOR, July 1991, p. 1241. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

Deckha. “Intersectionality and Posthumanist Visions of Equality.” Wisconsin Journal of Law, Gender & Society., vol. XXIII, no. 2, Nov. 2008, wjlgs.law.wisc.edu/2008/volume-xxiii-no-2.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research. “The Status of Black Women in the United States.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 26 June 2017, iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-Status-of-Black-Women-6.26.17.pdf.

Ramasubramanian, Srividya, et al. “Race and Ethnic Stereotypes in the Media.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, Oxford UP, Jan. 2023. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1262.

Walby, Sylvia, et al. “Intersectionality: Multiple Inequalities in Social Theory.” Sociology, vol. 46, no. 2, SAGE Publications, Jan. 2012, pp. 224–40. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416164.

Weathers, Mary Ann. “An Argument for Black Women’s Liberation as a Revolutionary Force.” No More Fun and Games: A Journal of Female Liberation, vol. 1, no. 2, Feb. 1969.

Weida, Kaz. “Black Feminism | Definition, History, Intersectionality, and Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Dec. 2023, http://www.britannica.com/topic/Black-feminism.

West, Carolyn, and Kalimah Johnson. “Sexual Violence in the Lives of African American Women.” vawnet.org, Mar. 2013, vawnet.org/sites/default/files/materials/files/2016-09/AR_SVAAWomenRevised.pdf.

Leave a comment