Even a week later, when I tried to reorganise the notes taken while reading The Handmaid’d Tale, I still could not get over the shock this astonishing, mind-boggling, spellbinding yet desperate book gave me. The Handmaid’s Tale is a novel by Canadian author Margaret Atwood, first published in 1985 (Wikipedia Contributors). The story’s background is set to be the future of America (which has turned into ‘the Republic of Gilead’), where most people lose their fertility due to heavy environmental pollution and radiation. As one of the few fertile humans, the protagonist (also the narrator of the story), Offred, is chosen to be a ‘Handmaid’ who, in actuality, is treated as the puppet of giving birth and reproduction (Atwood). The book, being in an autobiographical form, leads the audience on a journey in a totalitarian, dystopian, and religious society from Offred’s perspective.

Shortly after its release, The New York Times comments, ‘[It is a] ”forecast” of what we may have in store for us in the relatively near future (McCarthy)’ on Atwood’s masterpiece. In addition to its solid reputation in the Western world, in Chinese social media Douban, it placed 4th place in the rank of ‘Popular Feminist Literature Top 10’ (Douban). Indeed, when conducting the brief background research of The Handmaid’s Tale and reading the initial few pages of it, its literary techniques, involving narrative perspective and the introspective thoughts between lines, did mould my first impression of the book into the category’s ‘feminist literature’. Nonetheless, by following Offred’s detailed yet reflective statements, the dystopian core, anti-establishment stands and the questioning towards authority begin to float up.

In the world Offred living in, a fundamentalist power rules the society in a pyramid division of authority and status. Some individuals are forced to be the machines of child-bearing (‘Nor does rape cover it: nothing is going on here that I haven’t signed up for. There wasn’t a lot of choice but there was some, and this is what I chose.‘), some may be situated better (represented by the Commander who is ‘figuring out when his promotion is likely to be announced if all goes well.’ when the insemination is successful). However, regardless of the status of each of them, they all live a life of conformity under the totalitarian rule of religion holding Christian values. According to Michale Curtis, ‘totalitarianism’ is a term typifies ‘a particular genre of contemporary regime in an age of mass democracy in which the population can be controlled by a variety of means, especially terror.’ (Curtis). The ‘terror’ here is visualised by the executions in the story. Meanwhile, in Offred’s life, the dictatorship is symbolically constructed by religious values. It is maintained by the myth that the current circumstances will improve soon with collective efforts (‘The women will live in harmony together, all in one family…and when the population level is up to scratch again we’ll no longer have to transfer you from one house to another‘). According to Max Weber, the latter can be interpreted as a form of charismatic authority (Weber), which, in this case, refers to the Gilead government’s practice of constructing a ‘universal’ goal and blueprint, hence gaining the dominant position via its charisma.

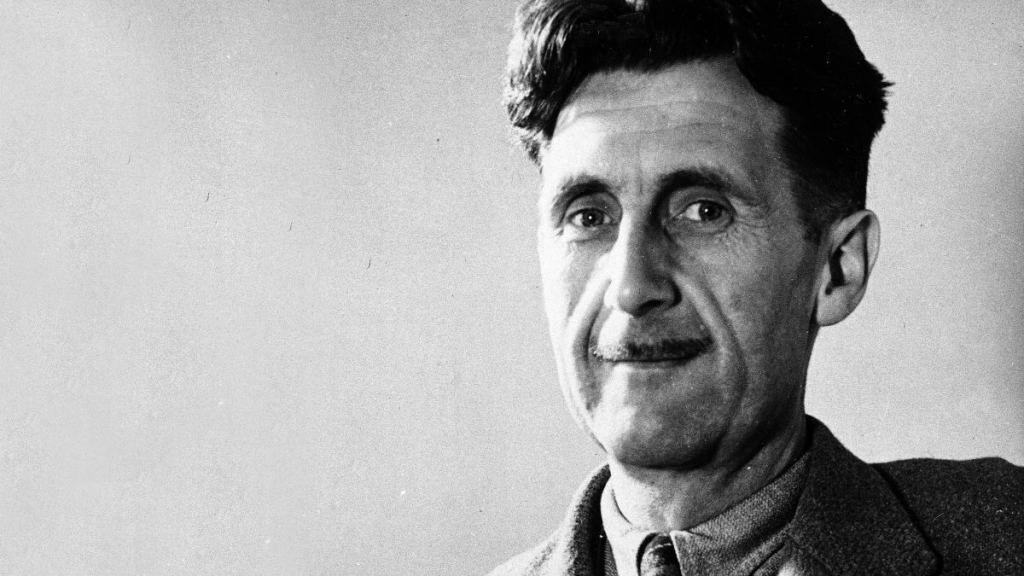

This inevitably reminds the reader of another dystopian book – George Orwell’s 1984. In both books, the masses are oppressed by the ruling class. They are deceived by lies, they live under constant surveillance (‘Big Brother’ in 1984 and ‘The Eyes’ in The Handmaid’s Tale), and the rights to read and write are severely restricted. – this blocking of critical information is also a form of obscurantism. Also, both employed numerous coinages, from ‘doublethink’ and ‘telescreen’ in 1984 to ‘econowives’ and ‘libertheos’ in The Handmaid’s Tale. By structuring and merging existing words, coinages allow for the features of the language to be further accentuated, thus capturing the reader’s inquisitiveness (Sutton-Spence). This innovation in words also echoes the future setting in which both stories occur. Apart from the level of setting, both choose a similar storyline throughout the text, that is, how, under intimidation and dehumanisation, people can maintain their final sobriety through lust, love and hate – just like the tangle between Winston Smith and Julia as well as the relationship between Offred and the Commander to which she belongs. Although both of these relationships come to a bad end, their role in shaping the character of the main character is undeniable (‘Such moments are possibilities, tiny peepholes.‘).

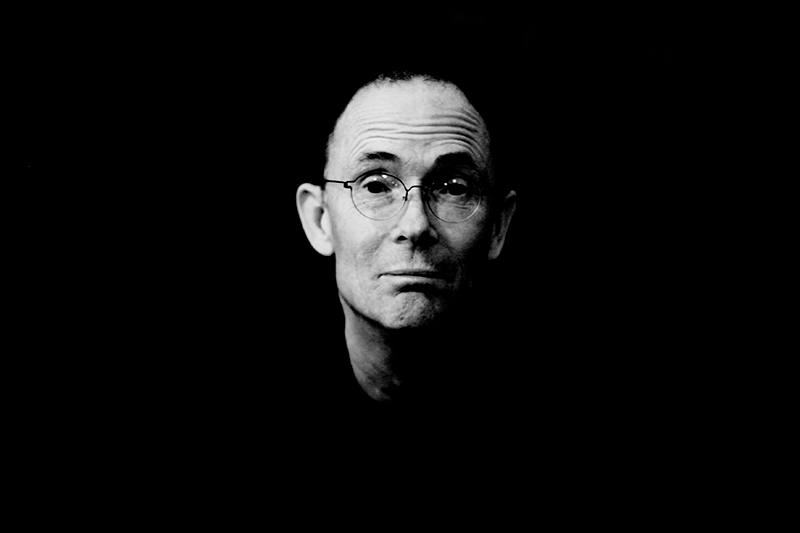

Besides, Atwood heavily relied on the stream of consciousness in the story. This makes sense because stream-of-consciousness techniques, with the assistance of parallelism, in autobiographical fiction can effectively capture the minute dynamics of stories. For instance, by revealing the story of Offred, her daughter and Luke, who was Offred’s husband before the formation of Gilead, readers will be able to become more aware of the impact this drastic change has had on her. In addition to the memories, the lines that suddenly interrupt the story’s pace also render a sense of isolation and alienation (‘You can mean thousands. I’m not in any immediate danger, I’ll say to you. /I’ll pretend you can hear me./But it’s no good because I know you can’t ‘) (‘We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.‘). William Gibson also employed those techniques in his iconic cyberpunk compositions Neuromancer and Burning Chrome, where the characters live in a high-tech world, but the connections and bonds between people weaken.

Overall, rather than digging hard into the literary and social science values behind The Handmaid’s Tale, it might have been a more rewarding exercise to bring yourself into the perspective of the main character, Offred, and navigate the brutal new world that Atwood writes about. Or perhaps, we are getting closer to society in the book.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. National Geographic Books, 1998, books.google.ie/books?id=LT2NEAAAQBAJ&dq=The+Handmaid%27s+Tale&hl=&cd=6&source=gbs_api.

Curtis, Michael. Totalitarianism. Transaction Publishers, 1979, books.google.ie/books?id=J7VGvQEACAAJ&dq=Totalitarianism+Curtis&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api.

Douban. “豆瓣热门女性文学图书TOP10.” Douban, m.douban.com/subject_collection/ECLMKLW4A. Accessed 9 Mar. 2024.

McCarthy, Mary. “Book Review.” The New Your Time, 9 Feb. 1986, archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/00/03/26/specials/mccarthy-atwood.html?module=inline.

Sutton-Spence, R. Analysing Sign Language Poetry. Springer, 2004, books.google.ie/books?id=QSDuCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=10.1057/9780230513907_5&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api.

Weber, Max 1864-1920. Politics as a Vocation. Hassell Street Press, 2021, books.google.ie/books?id=Ykm6zgEACAAJ&dq=Politics+as+a+Vocation&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api.

Wikipedia Contributors. “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Wikipedia, 1 Mar. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Handmaid%27s_Tale#CITEREFAtwood1985.

Leave a comment